Sixteen, fourteen, and twelve years old. Three sisters who did everything together, from daily chores to locking themselves in a room with a small temple, placing a chair by the window, and jumping one by one from the ninth floor at 2:15 in the morning. An eight-page suicide note. A diary where they called themselves “Korean princesses” and addressed each other by Korean names. And a final handwritten message: “We cannot leave Korea. Korea is our life.” This isn’t a story about gaming. This is a story about three children who disappeared into a digital world so completely that returning to reality seemed worse than death, and nobody noticed until it was too late.

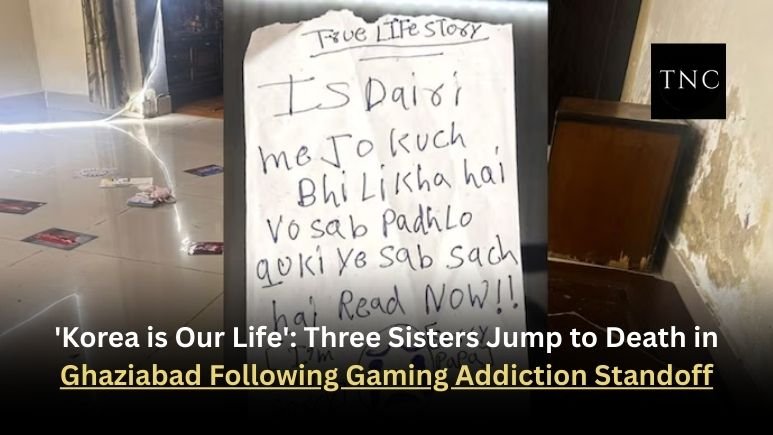

GHAZIABAD — A devastating tragedy has left the Bharat City Society in the Tila Mor area reeling after three minor sisters jumped to their deaths from the ninth floor of their residential tower early Wednesday morning, February 4, 2026. Nishika (16), Prachi (14), and Pakhi (12) were found lying in a pool of blood on the ground floor at approximately 2:15 AM, after neighbors and security guards were awakened by the sound of impact.

Despite being rushed to a hospital in Loni, all three were declared dead on arrival. What police discovered in the aftermath has sent shockwaves across the country and exposed the lethal intersection of digital addiction, educational neglect, parental desperation, and the complete failure of systems meant to protect vulnerable children.

The night it happened

According to Assistant Commissioner of Police Atul Kumar Singh, the sisters shared an “inseparable bond that transitioned into a shared delusion.” They did everything together throughout their lives, including making the decision to end those lives simultaneously.

The immediate catalyst was a confrontation with their parents. Their father, Chetan Kumar, a forex trader, had objected to what he called their “Love Game” addiction and had recently restricted their access to mobile phones. For girls whose entire identity had become wrapped up in a Korean task-based interactive app, losing phone access apparently felt like losing everything that mattered.

After the confrontation, the three sisters locked themselves in a room containing a small temple. Police found a chair placed near the window. The reconstruction suggests they jumped one by one, each sister following her siblings into the void.

Neighbors heard the thud. Security guards found the bodies. And by the time anyone could respond, three children were dead because nobody had figured out how to break through the digital prison they’d built around themselves.

The diary that explained everything and nothing

Investigators recovered an eight-page suicide note and a diary that revealed the depth of the sisters’ immersion in a parallel identity. They were so consumed by a Korean task-based interactive app that they had begun addressing each other by Korean names and identified themselves as “Korean princesses.”

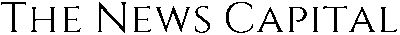

The final handwritten note is heartbreaking in its clarity:

“Is diary me jo kuch bhi likha hai wo sab padh lo kyunki ye sab sach hai. Read now!!! I’m really sorry. Sorry papa… we cannot leave Korea. Korea is our life.”

Translation: “Whatever is written in this diary, read it all because it’s all true. Read now!!! I’m really sorry. Sorry papa… we cannot leave Korea. Korea is our life.”

They knew they were causing pain. They apologized to their father. But the addiction, the alternate identity, the psychological dependency on this digital world was so complete that they genuinely believed they couldn’t survive without it. “Korea is our life” wasn’t metaphorical. It was literal truth from their perspective.

The educational failure nobody addressed

Here’s where this tragedy becomes even more disturbing. These girls had reportedly not attended school regularly since the COVID-19 pandemic began in 2020. That’s nearly six years of educational neglect.

| Sister | Age | Educational Status |

| Nishika | 16 | Enrolled in Class 4 curriculum (should be Class 11) |

| Prachi | 14 | Significant school absenteeism (should be Class 9) |

| Pakhi | 12 | Significant school absenteeism (should be Class 7) |

The eldest sister, Nishika, was 16 years old and struggling with Class 4 curriculum. That’s a seven-year educational gap. A 16-year-old working at an 8-year-old’s academic level indicates years of complete educational abandonment.

How does a child miss that much school without intervention? Where were the teachers following up on chronic absenteeism? Where were the school administrators reporting educational neglect? Where were the social services checking on children who simply disappeared from the education system?

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted schooling globally, but six years later, these girls were still not attending regularly. That’s not pandemic disruption. That’s systemic failure across multiple levels: family, school, community, and government agencies all failing to notice or act on children slipping through every safety net.

The addiction that consumed them

The girls were reportedly obsessed with what police are calling a “Love Game,” a Korean task-based interactive app. Cyber-security teams are now analyzing their phones to identify the specific application and trace whether external handlers might have influenced their actions.

Experts warn that many such games use psychological “hooks” to keep children addicted:

- Identity shifts: Allowing users to adopt alternate personas that feel more authentic or desirable than their real identities

- Task-based progression: Creating artificial sense of achievement and purpose through completing missions or challenges

- Belonging and community: Providing social connection and acceptance that users may not experience in their offline lives

- Escalating commitment: Gradually increasing time and emotional investment until users feel they’ve invested too much to quit

For children already isolated (not attending school, not developing real-world friendships, not engaging in normal adolescent activities), these digital worlds can become not just escapes but complete replacement realities.

The sisters calling themselves “Korean princesses” and using Korean names suggests they’d built entirely new identities within this game. They weren’t Indian girls living in Ghaziabad anymore. They were Korean characters living in a digital fantasy, and the real world had become the unwanted intrusion.

The Father impossible position

Chetan Kumar was in an impossible situation. He recognized his daughters had a problem. He tried to intervene by restricting phone access. And that intervention apparently triggered the crisis that ended in their deaths.

What was he supposed to do? Continue allowing unlimited access to a game that was clearly destroying their connection to reality? That would be negligent parenting. Restrict access and try to force them back into the real world? That’s what he did, and his daughters chose death over disconnection.

There’s no good answer when children are already this deep in addiction. By the time symptoms are severe enough for parents to recognize crisis-level problems, intervention often triggers resistance that can turn desperate. Professional help was needed long before restrictions on phone access became the breaking point.

The systemic failures

This tragedy didn’t happen overnight. It was the culmination of failures across multiple systems:

Educational system: Six years of chronic absenteeism without meaningful intervention. No follow-up on children disappearing from school. No social workers checking on educational neglect.

Healthcare system: No mental health support for children clearly showing signs of extreme social isolation and potential addiction. No accessible services for families dealing with digital addiction issues.

Technology regulation: Unregulated apps targeting minors with psychologically manipulative features designed to create dependency. No age verification, no screen time limits, no parental controls that actually work.

Community support: Neighbors and extended family apparently unaware of or unresponsive to three children completely withdrawing from normal life and education.

Family resources: Parents struggling to address severe addiction issues without professional support, guidance, or resources for intervention.

Each of these systems failed independently, but the compounding effect of multiple simultaneous failures created conditions where three children could spiral into fatal delusion without anyone successfully intervening.

The questions that need answers

Which specific app were they using? Who designed it? What psychological manipulation techniques does it employ? Are there other children similarly addicted? Have there been other casualties?

Why didn’t school authorities follow up on years of absenteeism? What are the protocols for chronic truancy, and why weren’t they enforced?

What mental health services are available in Ghaziabad for families dealing with digital addiction? If the father had sought professional help, would services have been accessible, affordable, and effective?

Are there other families right now struggling with similar issues, watching their children disappear into digital worlds, not knowing how to intervene before it’s too late?

The debate this reignites

The Ghaziabad tragedy will inevitably reignite fierce debate over regulation of apps targeting minors. Gaming companies will argue for parental responsibility and free market principles. Child safety advocates will demand age verification, time limits, and bans on psychologically manipulative features.

The truth, as always, lies somewhere between. Yes, parents have responsibility for monitoring children’s digital consumption. But when apps are specifically designed by behavioural psychologists to bypass rational decision-making and create dependency, expecting parents to successfully counteract that without support is unrealistic.

Regulation isn’t about banning technology. It’s about requiring basic safety standards: age verification that actually works, mandatory time limits for minor users, transparency about psychological manipulation techniques, and criminal liability for apps that target children with addiction-forming features.

The permanent consequences

Three girls are dead. A family is destroyed. And across India, parents are looking at their own children’s screen time with new fear, wondering if their kids are heading down the same path.

The “virtual” world had very real, very permanent consequences. Nishika, Prachi, and Pakhi believed “Korea is our life” so completely that losing access to that digital fantasy seemed worse than death. They apologized to their father but jumped anyway.

The silent hallways of Bharat City Society now stand as a grim reminder that children can disappear long before they physically leave. They can be sitting in the next room, staring at screens, while their real selves slowly dissolve into digital personas that feel more real than the bodies they inhabit.

And by the time anyone notices, by the time parents restrict access, by the time intervention happens, it might already be too late to bring them back from the worlds they’ve retreated into.

“Korea is our life.”

For three sisters in Ghaziabad, it was also their death.

Also Read / Wedding Horror in Pakistan: Suicide Bomber Kills 7 at Peace Leader’s Home.

Leave a comment