Abandoned walls in Mumbai’s poorest neighbourhoods. Dilapidated lanes where children worked instead of attending school. Communities where dropout rates meant most kids never finished even basic education, where “classroom” was a foreign concept and formal schooling seemed like something that happened to other people’s children. And one woman who looked at those walls and saw not decay but possibility, not barriers but canvases for curriculum. Rouble Nagi spent two decades transforming slum alleyways into open-air classrooms, painting 155,000 houses while teaching literacy, numeracy, hygiene, and science to over a million children who would never have set foot in a traditional school. Now she’s standing in Dubai accepting a $1 million prize and proving what educators have always known: the best teaching doesn’t always need a roof, a desk, or even walls. Sometimes the walls themselves become the teachers.

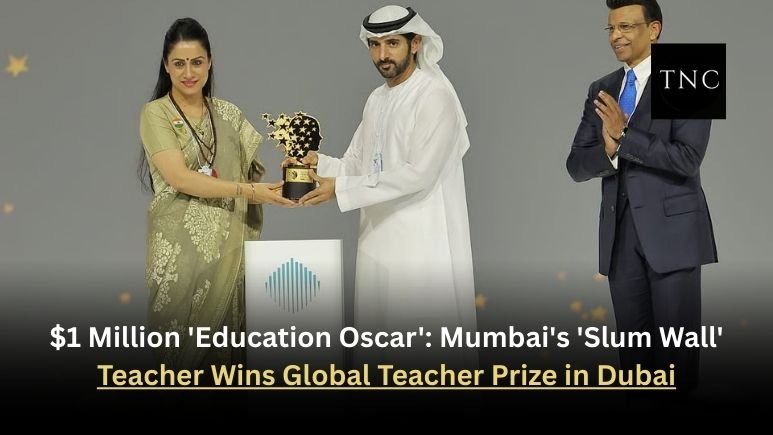

DUBAI, UAE — Under the glittering lights of the World Governments Summit 2026 on Thursday, February 5, 2026, Mumbai-based educator and activist Rouble Nagi was awarded the prestigious $1 million Global Teacher Prize, often called the “Education Oscar.” Presented by His Highness Sheikh Hamdan bin Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, Crown Prince of Dubai, and Varkey Foundation founder Sunny Varkey, the award recognizes Nagi’s extraordinary two-decade journey bringing literacy to India’s most underserved communities through her “Misaal India” program.

This isn’t a story about traditional teaching excellence in well-funded schools. This is about an artist-turned-educator who saw children invisible to the formal education system and decided that if they couldn’t come to school, she’d bring school to them in the most literal, visual, permanent way possible.

When walls become classrooms

Nagi’s teaching philosophy is built on a belief that challenges every assumption about how education happens: a child’s environment should be their first teacher. Where others saw abandoned walls and dilapidated lanes in Mumbai’s slums, she saw canvases for curriculum, surfaces waiting to be transformed into permanent learning tools accessible to every child in the community.

Her signature “Living Walls of Learning” aren’t decorative art projects. They’re interactive murals that teach literacy, numeracy, hygiene, and science. These permanent visual aids remain accessible to the community 24 hours a day, seven days a week. No need to enroll. No fees. No entrance requirements. Just walk outside your home and the walls themselves are teaching you to read, to count, to understand basic science, to practice hygiene that prevents disease.

Think about the genius of that approach. Traditional schools require children to come to a specific location at specific times, wear specific uniforms, bring specific materials. For children living in extreme poverty, working to help support their families, caring for younger siblings, or married off young, those requirements create insurmountable barriers. But a wall painted with educational content? That’s accessible to everyone, always.

The scale that transformed communities

Through the Rouble Nagi Art Foundation (RNAF), she’s established more than 800 learning centers across 100+ communities, focusing specifically on children who have never stepped into a formal school and likely never would without intervention.

Her “Misaal Mumbai” initiative began by painting over 155,000 houses. Let that number sink in. One hundred fifty-five thousand homes transformed simultaneously, improving sanitation and waterproofing while creating safe, vibrant spaces for learning. This wasn’t just education. This was community development, public health intervention, and infrastructure improvement all wrapped into one visually stunning package.

The murals teach practical knowledge that immediately improves lives. Hygiene practices that prevent disease. Nutrition information that helps families make better food choices with limited resources. Basic literacy that allows adults to read signs, documents, and instructions. Numeracy that prevents exploitation in markets and financial transactions.

Breaking the barriers keeping kids out of school

Nagi’s model directly addresses the systemic barriers that keep children out of formal education in India’s poorest communities:

Child labor: When families depend on children’s income for survival, traditional school with rigid hours and no immediate economic benefit isn’t viable. Nagi offers flexible schedules that allow children to learn while still contributing to family survival.

Early marriage: Girls particularly face pressure to marry young rather than continue education. By providing education that doesn’t require leaving the community or conforming to traditional school structures, Nagi created pathways for girls who would otherwise have been pulled out of learning entirely.

Lack of infrastructure: No school buildings nearby? No problem. The walls themselves are the school. No need for expensive construction, ongoing facility maintenance, or the political will to build schools in slum communities that often lack political representation.

Creative, hands-on learning: Using recycled materials, Nagi’s approach transforms trash into teaching tools, demonstrating that quality education doesn’t require expensive resources, just creativity and commitment.

The measurable impact that matters

These aren’t just feel-good stories. The numbers demonstrate genuine educational transformation:

| What Changed | The Impact |

| Prize amount | $1 million USD |

| Children reached | Over 1 million |

| Learning centers established | 800+ across 100+ communities |

| Houses painted/improved | 155,000+ |

| Dropout rate reduction | Over 50% in served communities |

| Educators trained | 600+ volunteers and paid teachers |

That 50%+ reduction in dropout rates is particularly significant. In communities where completing even basic education was rare, halving the dropout rate means thousands of children staying in school who otherwise would have left, gaining literacy and numeracy skills that fundamentally change their life trajectories.

The long-term school retention improvement for girls specifically addresses one of India’s most persistent educational inequities. Girls in poor communities face extraordinary pressure to leave school for marriage, domestic work, or family care responsibilities. Programs that successfully keep girls in school longer create ripple effects across generations, as educated mothers are more likely to prioritize education for their own children.

Beyond the children: community transformation

Nagi hasn’t just taught children. She’s trained over 600 volunteer and paid educators, empowering local residents to take charge of their own neighborhoods’ development. This model creates sustainability that outside interventions rarely achieve. When community members themselves become the teachers, the program doesn’t depend on a single charismatic founder. It becomes embedded in the community’s identity and capacity.

The house painting initiative created community pride in neighborhoods that had been written off as eyesores. When your home is painted with beautiful, educational murals instead of covered in grime and decay, the psychological impact extends beyond aesthetics. It sends a message: your community matters, your children matter, your education matters.

What she’ll do with $1 million

Nagi is the 10th recipient of the Global Teacher Prize, following previous Indian winner Ranjitsinh Disale. She’s clear about how she’ll use the money: scaling impact further.

“This gives me the momentum to go further, reaching more children, breaking down barriers, and ensuring every learner can not only access education, but stay and succeed,” she stated after receiving the award.

Her immediate goal is establishing a Training and Skilling Institute providing free vocational and digital literacy training to marginalized youth. This addresses the gap between basic education and 21st-century employment. Learning to read and do basic math is essential, but young people also need practical skills that translate to jobs in India’s evolving economy.

Digital literacy particularly matters. India’s economy is increasingly technology-dependent, and children from slum communities who gain basic literacy through wall murals still need digital skills to access opportunities in the modern job market. Nagi’s Institute would bridge that gap, providing pathways from basic literacy to employable skills.

The model that challenges everything

What makes Nagi’s work so significant isn’t just the scale or the numbers, though those are impressive. It’s the fundamental challenge to assumptions about how education must happen.

Traditional education reform focuses on building more schools, training more teachers, reducing class sizes, improving curriculum, providing textbooks. Those are all valuable, but they assume education requires formal institutional structures that many communities lack and may not acquire for decades.

Nagi demonstrated that education can happen anywhere with creativity and commitment. Walls become textbooks. Alleys become classrooms. Recycled materials become teaching tools. Community members become educators. And suddenly, children who were completely outside the formal education system are learning, staying in school, and gaining skills that change their lives.

This isn’t a replacement for formal education. It’s a bridge for children who would never reach formal education without intervention. Many of Nagi’s students have successfully transitioned into traditional schools after gaining basic literacy through her programs. She’s not competing with formal education. She’s creating pathways to it for children who were excluded.

Why this matters beyond Mumbai

Globally, hundreds of millions of children remain outside formal education systems because of poverty, conflict, discrimination, lack of infrastructure, or cultural barriers. Traditional solutions, building schools and training teachers, are important but insufficient for reaching the most marginalized.

Nagi’s model is scalable and adaptable. Walls exist everywhere. Communities everywhere have residents who could be trained as educators. Recycled materials are universally available. The specific implementation would vary by context, but the core principle, using the physical environment itself as a teaching tool and bringing education to children rather than waiting for children to come to education, applies globally.

The $1 million Global Teacher Prize brings international attention to an approach that could be replicated in slums, refugee camps, rural villages, and other contexts where traditional schooling remains out of reach for the most vulnerable children.

The artist who became an educator

Nagi started as an artist and brought an artist’s eye to education’s challenges. She saw beauty and possibility where others saw decay. She understood that visual learning is powerful, that environment shapes cognition, that permanent installations accessible 24/7 reach more children than time-limited classroom sessions.

Her transition from artist to educator demonstrates that the best educational innovation sometimes comes from outside traditional education systems. People unconstrained by “this is how we’ve always done it” can reimagine what teaching and learning look like.

Standing in Dubai accepting the Global Teacher Prize, Rouble Nagi represents not just her own extraordinary achievement but a broader truth: education belongs to children who’ve never seen a classroom just as much as it belongs to children in expensive private schools. And sometimes, getting education to those invisible children requires not building more schools but painting more walls, not training more traditional teachers but empowering more community members, not buying more expensive materials but creatively using what’s already there.

A million dollars. A million children. And proof that the best classrooms might not have roofs at all.

Also Read / Abu Dhabi Breakthrough: Ukraine and Russia Face Off in First Direct Peace Talks.

Leave a comment